Minimal Overhead Messaging Support Using Runtime Agnostic Memory Layouts

Abstract

This REP proposes a re-design of the rosidl messaging system to broaden the scope of application of zero-copy transports, including those that deal with seggregated memory models. In particular, it specifies message in-memory representations and middleware extensions to enable runtime-agnostic contiguous memory layouts that can be passed around across process boundaries with minimal overhead.

Motivation

rosidl is one the oldest subsystems of ROS 2. Initial research dates back to 2013. C and C++ message generators were first released with Alpha 1, each with their own runtime representations. Language-specific, member-based interfaces were simple enough to implement and verifiably performant. The first few DDS based middlewares had their own vendor-specific IDL to comply with, for interoperability and full feature support, and their own wire formats, thus some data processing (ie. copy, conversion, serialization) cost had to be paid one way or another and it was deemed affordable.

rosidl design hasn’t changed substantially since then. Unfortunately, even if well suited for ROS systems distributed over many hosts in a network, its simplicity sacrifices performance for the fairly common single host topology.

Autonomous systems can produce vast amounts of data in a relatively short span of time and every non-functional data processing step (copy, conversion, serialization) slows down data transport up to a complete halt if data paths are not carefully designed. Multiple features have been added to ROS over time to optimize these data paths: message loaning, shared memory transports, intra-process communication, type adaptation and negotiation. Many of these features simply implement some often narrow form of so called zero-copy data transport: moving data from peer A to peer B with minimal overhead.

Yet the rosidl design precludes full application of more general forms of zero-copy data transport. As of early 2026, middlewares that feature zero-copy data transport cannot cross the language boundary because there’s no common runtime representation, and because in-memory layouts are nonlocal for variable-length members, even for the same language the scope of application is extremely narrow. So narrow not even standard messages like std_msgs/msg/Header qualify. Adoption therefore remains low, all the while rclcpp intra-process communication is widely acknowledged as a key enabler for the most demanding applications.

rosidl design must change to properly accomodate zero-copy data transport.

Specification

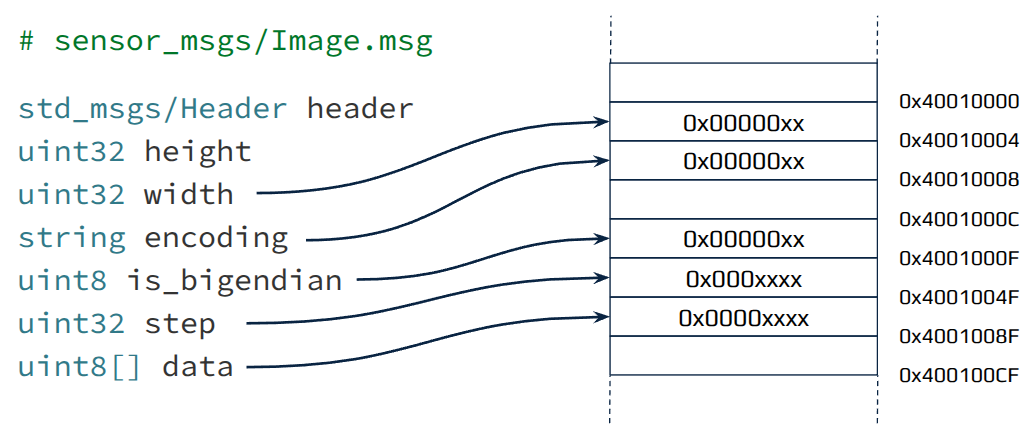

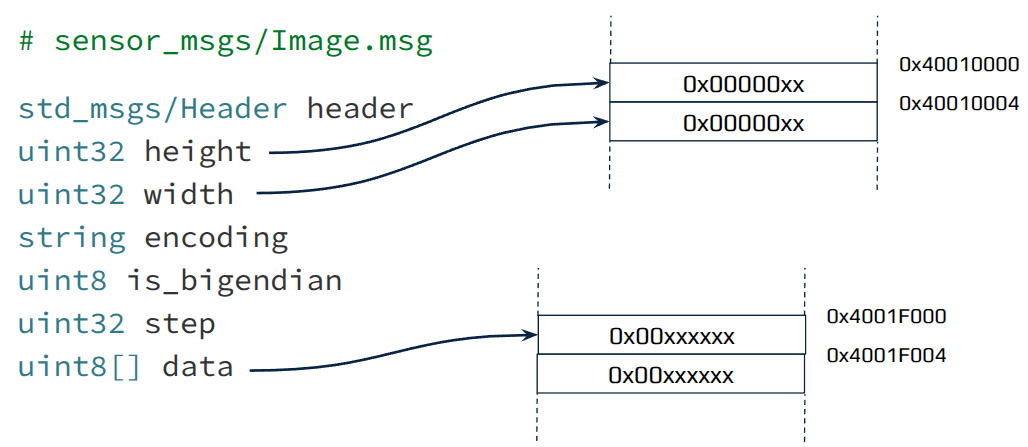

The proposed re-design hinges on one central idea: rosidl messages as language-specific views to language-agnostic contiguous memory layouts, bounded on write (ie. publish), unbounded on read (ie. subscription).

Three (3) abstractions are introduced to generated code for rosidl messages (including request-response message pairs for services): views, storage, and shapes.

Views

Language-specific data interfaces or views rather than data structures. Instead of relying on language-specific memory management and layout, these data views provide semantically meaningful, idiomatic access to otherwise raw memory. Data views may own the memory they point to (e.g. when default constructed) or simply bear a reference to it (e.g. when externally managed, perhaps loaned):

Storage

For each message member, the underlying blob of memory is wrapped by a rosidl_memory_t data structure:

1

2

3

4

typedef struct rosidl_memory {

void *address;

int attributes;

} rosidl_memory_t;

Note this data structure assumes a flat (i.e. non-segmented) memory space. Attributes qualify the blob e.g. which device it has been allocated to, which memory section it was allocated from (if any), what operations are permitted on it, etc. This helps code path selection when managing the specifics of that memory e.g. for to_cpu() implementations that may result in memory transfers. TBD: should there be generic APIs to manage (de)allocation?

This abstraction enables different memory management techniques and patterns: segregated memory for fixed-size members allocation; memory alignment for cache locality and vectorization, particularly for sequence members; plain dynamic allocation for variable-length members as expected from current rosidl. It can handle multiple memory spaces in heterogenous compute applications. It can also encode references, casting memory layouts well suited for the underlying transport. For shared-memory transports, a contiguous memory block is often best. For network transports, keeping this casting zero-cost requires binary compatibility between the message in-memory representation and the serialization format. Endianness, alignment, padding must match.

To help data view construction when memory is externally managed, language-specific storage data structures matching their corresponding message layout are introduced. These data structures organize the underlying memory for consumption. A single rosidl_memory_t structure is used for each POD member, string member, and POD sequence member, whereas sequences of rosidl_memory_t structures are used for sequence of string members, and the corresponding storage data structures are used for message members and sequences thereof. E.g.:

1

2

3

4

5

6

struct sensor_msgs::msg::Image::Storage {

std_msgs::msg::Header::Storage header;

rosidl_memory_t width;

// ...

rosidl_memory_t data;

};

Shapes

To help data storage allocation when memory is externally managed, language-specific shape data structures matching their corresponding message layout are introduced. These data structures constrain variable-length members to a given size and thus partially characterize the memory footprint of the message (as fixed-size members’ contribution is implied and the underlying implementation may still pad and align as need be). A size_t value is used for each string and POD sequence member, whereas sequences of size_t values are used for sequence of string members (and eventually tensor members). For message members and sequences thereof, the corresponding shape data structures are used in liue of size_t. E.g.:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

typedef struct rosidl_sized {

size_t size; // as an aggregate for better readability

} rosidl_sized_t;

struct sensor_msgs::msg::Image::Shape {

std_msgs::msg::Header::Shape header;

rosidl_sized_t data;

};

In this re-design, message shapes are not communicated explicitly. Sizes of variable-length members must be encoded within the chosen in-memory representation. A binary compatible and descriptive serialization format is a valid option and the chosen one for the reference implementation put associated to this REP.

Middleware changes

One (1) change is introduced to rmw APIs. Message shapes may be provided to publishers and subscriptions on construction, through options. Implementations can then optimize (and optionally check) for bounded messages, upon loan or else:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

typedef struct RMW_PUBLIC_TYPE rmw_subscription_options_s {

// ...

void * message_shape; // defaults to NULL

// ...

} rmw_subscription_options_t;

typedef struct RMW_PUBLIC_TYPE rmw_publisher_options_s {

// ...

void * message_shape; // defaults to NULL

// ...

} rmw_publisher_options_t;

rmw implementations may then use this additional information to optimize message transport. TBD: should device specifics be communicated at this point too?

Rationale

Middlewares that feature zero-copy data transport can implement message loaning APIs and rely on message type support to determine the size of the allocation and delegate message construction.

ROS nodes that publish data can leverage these APIs by specifying the shape of the message they intend to publish. This is reasonable in many cases e.g. for sensor drivers with preconfigured resolution. By constraining the size of variable-length members, memory locality can be achieved. ROS nodes that subscribe data need not know about any shape, as the resulting memory layout remains structurally consistent with the message layout. Furthermore, since the underlying memory layout can stay the same regardless of the nature of the view, this design affords cross-language zero-copy data transport by construction.

Language-specific views, storage, and shapes imply language-specific type support code. While choosing one language for a reusable implementation that can be bound by the rest remains an option – an option exercised by the rosidl_generator_py package – it is hypothesized that fully decoupling these abstractions just above the serialization format will result in simpler generated (and generating) code.

Backwards Compatibility

In order to ensure both owning and non-owning (i.e. referencing) views offer a consistent interface, this re-design must abandon standard library types. In high-level programming languages like C++ and Python, sequence and string member types that are functionally equivalent (but not type equivalent and thus API incompatible, strictly speaking) to their standard counterparts (i.e. std::vector, builtin.list) can be implemented. Access patterns resembling the current member-based approach can also be worked out. In programming languages like C, this is impossible and this re-design will necessarily break backwards incompatibility.

While languages like C++ and Python can afford a softer transition via inline namespacing and import tricks, languages like C lack such features and thus an implementation shall ensure over-the-wire compatibility whenever possible. This provides a forward migration path: new code and old code can coexist while the new progressively replaces the old.

How to Teach This

A primary goal of this re-design is to be maximally compatible with the current interfaces and programming patterns. User application should not require training other than that for standard ROS, with additional implementation notes at most to signal the higher performance path these changes open up:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

#include <rclcpp/rclcpp.hpp>

#include <sensor_msgs/msg/image.hpp>

class LoanedImagePublisher : public rclcpp::Node {

public:

LoanedImagePublisher()

: Node("loaned_image_publisher")

{

sensor_msgs::msg::Image::Shape vga_image_shape;

vga_image_shape.encoding.size = 4;

vga_image_shape.data.size = 640 * 480;

rclcpp::PublisherOptions options;

options.shape = &vga_image_shape;

publisher_ = this->create_publisher<sensor_msgs::msg::Image>("image", 10, options);

timer_ = this->create_wall_timer(

std::chrono::milliseconds(100),

std::bind(&LoanedImagePublisher::publish_image, this));

}

private:

void publish_image()

{

auto loaned_msg = publisher_->borrow_loaned_message();

auto & msg = loaned_msg.get();

msg.width = 640;

msg.height = 480;

msg.encoding = "rgb8";

msg.data.assign(msg.width * msg.height * 3, 0);

publisher_->publish(std::move(loaned_msg));

}

rclcpp::Publisher<sensor_msgs::msg::Image>::SharedPtr publisher_;

rclcpp::TimerBase::SharedPtr timer_;

};

int main(int argc, char ** argv)

{

rclcpp::init(argc, argv);

rclcpp::spin(std::make_shared<LoanedImagePublisher>());

rclcpp::shutdown();

return 0;

}

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

import rclpy

from rclpy.node import Node

from sensor_msgs.msg import Image

class LoanedImageSubscriber(Node):

def __init__(self):

super().__init__('loaned_image_subscriber')

self.subscription = self.create_subscription(

Image, 'image', self.listener_callback, 10

)

def listener_callback(self, msg):

self.get_logger().info(

f'Received image: {msg.width}x{msg.height}, encoding={msg.encoding}'

)

def main(args=None):

rclpy.init(args=args)

node = LoanedImageSubscriber()

try:

rclpy.spin(node)

finally:

node.destroy_node()

rclpy.try_shutdown()

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

On the other hand, developer guides will be necessary to maintain and evolve the implementation over time. Complete guides for language and type support implementation are a must, and the reference implementation brings its own.

Implementation

Reference implementation can be found at TBD.

For the reference implementation, XCDRv1 is chosen as the serialization format (and thus as the in-memory representation for message views) for a number of reasons:

- It is binary compatible. XCDRv1 serializes full sized data sequentially, and while big endian by default, it can be configured to operate in little endian like the vast majority of modern compute platforms.

- It is sufficiently descriptive. XCDRv1 serializes enough information (i.e. alignments, sizes) to recover the message if its structure is known.

- It ensures over-the-wire compatibility. At the time of writing of this REP, most RMW implementations, including all Tier 1 RMW implementations, use XCDRv1 as serialization format. Messages exchanged by processes using the proposed re-design and the original design will be mutually intelligible. TBD: should we be using XCDRv2? Append-only message extension would be easier to support.

- It is feature complete. The IDL specification that XCDRv1 was designed to support is a superset of that of

rosidl, including mechanisms for messages to evolve over time.

TBD is chosen as the target middleware, featuring both shared-memory and network transports to put the messaging system to test in relevant operating conditions.

Message runtime APIs are devised so as to be functionally equivalent (or approximately so) to those of the original rosidl design. Member-based access is kept, relying on language-specific forms of the data descriptor pattern. This is trivial in Python, where @property is a thing, but a bit less so in C++:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

template <typename T>

struct rosidl_runtime_cpp::Property {

// ...

operator T() const {

return *reinterpret_cast<T*>(buffer->data);

}

T& operator=(const T& value) {

T& storage = *reinterpret_cast<T*>(buffer->data);

storage = value;

return storage;

}

private:

rosidl_memory_t buffer;

};

struct sensor_msgs::msg::Image {

std_msgs::msg::Header header;

rosidl_runtime_cpp::Property<uint32_t> width;

// ...

};

sensor_msgs::msg::Image message;

message.width = 640;

and significantly harder in C:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

struct rosidl_runtime_c__uint32_property_t {

uint32_t value;

};

struct sensor_msgs__msg__Image {

std_msgs__msg__Header header;

rosidl_runtime_c__uint32_property_t *width;

// ...

/*implementation-defined*/ __impl;

};

sensor_msgs__msg__Image message;

sensor_msgs__msg__Image_init(&message);

message.width->value = 640;

where __impl may be a type-erased reference or a nested struct where rosidl_memory_t instances may be stored and handled by the associated message functions.

Standard language constructs and data structures are used whenever possible. Duck typing in Python is rather forgiving; much can be done with memoryview and the array protocol. C++ is not, and thus std::array, std::vector, std::string, and std::wstring are replaced with rosidl_runtime_cpp equivalents with a rosidl_memory_t backbone.

Deviating from standard practice, message type support APIs are cast into a uniform set through virtual tables, allowing for message size computations and construction and casting in place as well as standard (de)serialization in any implementation:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

/// Computes message size given its type and shape.

rcutils_ret_t

rosidl_typesupport_get_expected_message_size(

rosidl_message_type_support_t * type_support,

void * shape, size_t * size);

/// Computes a given message size.

rcutils_ret_t

rosidl_typesupport_get_message_size(

rosidl_message_type_support_t * type_support,

void * message, size_t * size);

/// Constructs a message of a given type and shape at the given storage.

/**

* Can be understood as pre-serialization procedure.

* Storage size is assumed to be adequate, as returned by

* rosidl_typesupport_get_expected_message_size() for the

* same type and shape.

* Message members are default initialized.

* Message lifetime is to be managed by the caller.

*/

rcutils_ret_t

rosidl_typesupport_construct_message_at(

rosidl_memory_t * storage,

rosidl_message_type_support_t * type_support,

void * shape, void ** message);

/// Casts a memory blobin storage into a message of a given type.

/**

* Can be understood as a zero-copy deserialization procedure.

* Variable-length message members details are retrieved from the blob.

* Message encodes references to (i.e. borrows from) storage.

* Message lifetime is to be managed by the caller.

*/

rcutils_ret_t

rosidl_typesupport_cast_message_at(

rosidl_memory_t * storage,

rosidl_message_type_support_t * type_support,

void ** message);

/// Deserializes a message of a given type from storage.

/**

* Plain deserialization.

* Message manages dynamically allocated members, not necessarily contiguous.

* Message lifetime is to be managed by the caller.

*/

rcutils_ret_t

rosidl_typesupport_deserialize_message_from(

rosidl_memory_t * storage,

rosidl_message_type_support_t * type_support,

void ** message);

/// Serializes a message of a given type into storage.

/**

* Plain serialization.

* Storage size is assumed to be adequate, as returned by

* rosidl_typesupport_get_message_size() for the same message.

*/

rcutils_ret_t

rosidl_typesupport_serialize_message_into(

rosidl_message_type_support_t * type_support,

void * message, rosidl_memory_t * storage);

Note these APIs do not fiddle with message specific storage data structures. Future extensions may allow for more sophisticated memory management strategies.

Rejected Ideas

- Replace

rosidlwith a different data interchange technology, featuring the missing bits for cross-language zero-copy transport (e.g. FlatBuffers). While tempting, such a change would completely break compatibility. Breaking API, ABI, and over the wire compatibility across the board for an ecosystem as vast as that of ROS would result in either limited community adoption or fragmentation.

Known Issues

TBD

Copyright/License

This document is marked CC0 1.0 Universal. To view a copy of this mark, visit https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/.